To Train Or Not To Train

I have a set session, but I feel terrible, what do I do…

When we train regularly, we create a high level of physical fatigue. On top of our training we have other stressors in our lives that we need to balance so that we can adapt to our training and grow stronger. Some days the balance is not quite right and training could be counterproductive. If we train in this state for too long, we’ll very likely end up ill or injured putting our race plans in jeopardy.

Firstly, there are many different considerations to this question; Are you sick? Are you tired? Is it muscle soreness? Is it chronic or acute fatigue? How much sleep did you get last night? What sessions did you do yesterday? What did you do the day before yesterday? How much stress is in your life right now?

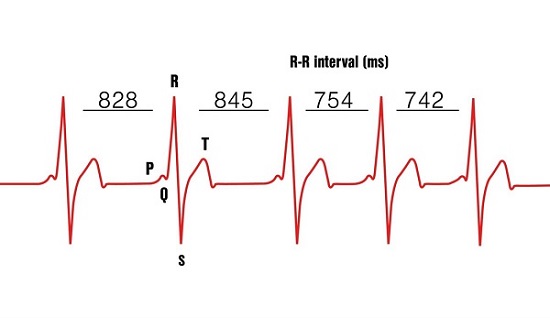

Fitness technologies have opened up a vast array of possibilities to asses and quantify your training load through monitoring the variables like sleep, using software platforms like Training Peaks to determine CTL (Chronic Training Load), TSB (Training Stress Balance), or measuring HRV (Heart Rate Variability) and resting heart rate. Having clear consistent data with these variables will help you and your coach keep informed as to where you’re at.

Resting HR, and now HRV, will give you some great data to help you see whether you’re in a fatigued state - it could indicate the need to back off training and go for more recovery. These two variables can also be an indicator of whether you have too much stress in your life, which you also need to consider as a reason to back off from training.

Heart Rate Variability

Linking to HR and HRV, taking note of your CTL and TSB is important. As a general rule if your TSB has consistently been lower than -20 for longer than two weeks it would be a good idea to back off and freshen up a touch. This could be just aerobic training instead of intensity but may also require a day off. These variables are of course individual and require you to know where your points of over-training are.

A further link to overall stress, and often a cause of sickness, is lack of sleep. Sleep is your KEY component to recovery. If you’ve been getting less than 8 hours and regularly getting up very early then the amount of REM sleep you’ve acquired will be limited, severely impacting recovery. 3+ days in this state, on top of training, can often lead to a place where you are susceptible to illness or experiencing greater fatigue from a training session. Take your sleep history into account when making a call if you carry on your weekly plan.

Sickness… there is often debate as to whether exercise will make your sickness better or worse. Obviously, the extent of your illness plays a part, and the weather conditions you might be going out in will inform your decision more! Raining and 2 degrees is probably not going to end up well…excuse the pun!

The most frequent decision lies around a common cold, and as a rule of thumb we often ask if it’s in your chest. If not, then you’re usually good to go for aerobic training only. If it’s in your chest then it’s best you miss the session altogether. We do often make an exception for swimming, cutting it out for all levels of colds, as historically it seems to make colds worse.

So, when assessing your ‘readiness to train’, data can be of great value, however so can an honest, objective, morning assessment. Knowing when to make the smart decision to train when the body is ready, or alternatively rest when you’re too fatigued, can be helped by using the following 0-10 fatigue scale every day to watch out for warning signs.

This can be done by rating various indicators of the early warnings of overtraining or that the body for whatever reason isn’t recovering from the training workload. Do this at the start of every day because it's when waking first thing in the morning that they are usually most obvious. If you do this at the start of every day it provides feedback on how your stress-recovery balance is going.

The table lists several common potential warning signs. Have this table by your bed and first thing in the morning, before getting up, quickly scan the list and reply ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ to each question. Be instinctive and answer immediately based on your first reaction. We aren't talking about subtle nuances here, only that you're experiencing a fatigue-warning sensation (‘yes’) or you’re not (‘no’).

Note the ‘Yes Score’ every time you answer yes and add up the yes scores for the day. If the total is less than 7 it's a normal training day ahead for you. But if the score is higher you need recovery. That could be active recovery (e.g. easy swim or ride) or passive (a day off).

*For Resting HR question, you must know what your typical average resting hr is when in a low training phase

Any one of these warnings by itself is probably not enough to warrant a recovery day, unless it’s extreme. For example, that could be the ‘health’ warning. If you wake up with a sore throat, regardless of your total score, it’s probably a good idea to significantly lower the stress that day. It's the total weight of several warnings that tells you how great the fatigue is and that recovery is needed.

Lastly, if you feel you really can probably do a training session what might you change? Firstly, we might look to drop out any anaerobic or anaerobic glycolytic work. This work often requires high levels of freshness to get the most out of it, so therefore why do it fatigued? Then we start to consider threshold and tempo / steady state sessions. If you’re just feeling flat and data indicates you’re ready to go, then likely you can hit threshold and tempo sessions. If the data and / or you say otherwise, you likely won’t get through a high stress threshold session but you may get away with a tempo / steady state workout.

In summary, a key part of the decision making is knowing the data or being honest in your daily physical assessment so you can make the most informed decision, especially as you learn to understand your daily recovery needs.

Tim Brazier

LINKS:

Heart Rate Variability App at https://www.hrv4training.com/

CTL / TSB / TSS are all acronyms at https://www.trainingpeaks.com/

Readiness to Train adapted from Joe Friel at https://www.joefrielsblog.com/